|

A Face for the Monster:

The Universal Pictures Series

Frankenstein (1931)

Cover of 1999 DVD release of Frankenstein

|

Perhaps the longest-lasting and most memorable image of Frankenstein and his Monster was

created in 1931, when Universal Pictures released what is now often

praised as the definitive horror film: Frankenstein.

The image of Boris Karloff

in the flat-head monster mask with bolts in his

neck and in undersized clothes has become part of popular culture; even

little children are familiar with it and by today Boris Karloff's iconic impersonation

of the Monster has become synonymous with the word

"Frankenstein".

But before filming began on 24 August 1931 a long period of

pre-production preceded. At the end of the 1920s Universal Pictures, which

was

founded in 1912 by Carl

Laemmle Sr, a Jewish German immigrant, was still a small studio.

Nevertheless Universal had achieved a reputation as the sole creator

of the horror film genre. Low-budget productions like The

Hunchback of Notre Dame, The

Phantom of the Opera and Dracula

had established it as the leading studio of the genre and had made actors like

Lon Chaney and Bela Lugosi famous. In 1930 French-born director Robert

Florey was hired by Universal to develop a new horror film as a follow-up to

the highly successful Dracula.

The studio had acquired the rights to Peggy Webling's theatre adaptation

Frankenstein: An Adventure in the Macabre, which had become a huge

success in London in the late 1920s. Bela

Lugosi, star of Universal's Dracula, was cast as the Monster, but later turned down the role

because he did not want to play a character that did not utter a single

word. (Another source, the Hollywood Filmograph magazine, stated in

January 1932 that Lugosi did not want the role because

he

thought that "physically he was not strong enough to give the strength

and power to the characterization").

First test screenings with Lugosi did not satisfy producer Carl Laemmle Jr and director

James Whale

was hired to replace Florey. Whale, an acclaimed director, chose

44-year old Boris Karloff as the Monster and together with make-up

specialist Jack Pierce they created the most influential horror image of

all times.

|

Synopsis:

|

The

film begins with Henry Frankenstein and his hunchback assistant Fritz

stealing a body from a grave and another from the gallows. Later Fritz is

sent to a medical university where he is to steal a brain for

Frankenstein's creature. He accidentally drops the glass jar with the

brain and instead takes another, oblivious to the jar's label "abnormal

brain". Meanwhile Frankenstein's fiancée Elizabeth and his friend

Victor plan to visit Frankenstein in his laboratory. After receiving

a strange letter from Henry, Elizabeth becomes worried about Victor. Dr.

Waldman's revelation, that her husband-to-be has left university and was

involved in strange experiments only makes her more anxious. The trio

arrive just in time to attend Frankenstein's final experiment, the

creation of an artificial human being, which Frankenstein animates by

exhibiting it to electricity created by a thunderstorm. Unfortunately, the

creature turns out to be an ugly and dumb brute unable to utter a single

word. When the enraged creature becomes troublesome Frankenstein locks it

away in the cellar. But the Monster, repeatedly abused by Fritz with a

whip and a torch, breaks free, kills Fritz and Dr. Waldmann and

escapes. Meanwhile Frankenstein, believing his creature to be destroyed by

Waldmann, prepares for his

wedding with Elizabeth. The joyful event is

suddenly wasted when a peasant father arrives in the village carrying his

murdered daughter Maria. Soon a lynch mob lead by burgomaster Vogel and

Frankenstein leaves to kill the Monster. In the mountains Frankenstein and

his creature finally meet. The Monster drags his creator into an old

windmill and throws him down the walls. Frankenstein's fall is weakened by

a blade of the mill and he survives. The enraged citizens set the building

on fire where the Monster is supposedly burnt to death. |

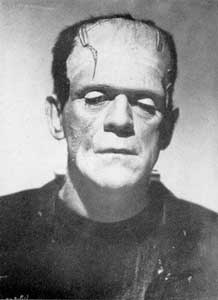

Boris Karloff as the Monster

|

Frankenstein finally opened on 4 November 1931 at the Mayfair Theatre

in New York's Time Square and caused an immediate sensation. It was voted

one of the films of the year by the New York Times and earned Universal

Pictures $ 12 million - the production had cost only $ 262 000. This made it

an even bigger success than Dracula one year earlier.

|

Its controversial content, in particular scenes depicting violence and

dialogue which was deemed to be blasphemy (e.g. Frankenstein's line "Now

I know what it's like to be God!"), made sure that

Frankenstein would run into trouble with censorship boards all over the

world. Although on first release the US federal censor didn't demand any cuts, several

US states only

showed edited versions of Frankenstein.

In Kansas City the State Board of Censors demanded 32 cuts and in Rhode

Island newspapers refused to run advertisements for the movie. In Britain

censors cut out the scene where Frankenstein discovers Fritz's hanged

body, a scene of the Monster threatening Elizabeth and the murder of Dr. Waldmann. But

when Frankenstein was re-released in the USA in 1937 Universal were forced to cut

several scenes, including one where the

Monster kills the little girl Maria - undoubtedly one of the film's key

scenes. Movie fans had to wait until 1985 to see a restored version of the

film including all previously trimmed scenes. All current versions

released on DVD and VHS contain this uncut version, although some TV

broadcasts may still be based on older, censored prints. |

The Monster kills the little girl - not in the

censored print

|

When Garret Fort and

Francis Faragoh wrote their version of the Frankenstein story they made considerable changes

from the original novel to the screenplay, and in fact used Webling's

theater play as their primary source. These changes in

content can be seen as a result of the transformation of the story in medium and

audience. The Gothic novel aimed at a

particularly middle-class audience whereas a film like Frankenstein

is made for a mass audience (1). The shift in medium from written text to film

results in the dropping of all narrative frames from Mary Shelley's

text. The confusing presentation and juxtaposition of several viewpoints

(Walton's, Frankenstein's, the Monster's) would not be manageable in a

film, at least not in a commercially orientated product like Frankenstein

in the 1930s.

The first obvious change in the story is the dropping of the Walton-frame. This results in a considerable narrowing of possible

interpretations of the story. Since Walton's point of view is

removed we only have Frankenstein's own experience left. This single point

of view fits easily in a conservative model of science that warns us of

setting mankind above nature or God's creation. Therefore the film serves

as a reinforcement of conservative values and reactionary views, a

tendency that has dominated Hollywood cinema from its beginnings to the present.

Of

course the most important changes from novel to film involved the

character of the Monster. In the

novel the Monster is humanised whereas the film tries to dehumanise him.

By making him a mute and violent fiend, for the audience any chance of identification with

him is gone. Boris Karloff's creature is a sub-human, barely capable of any

other emotion than rage and violence. He responds only to simple orders,

he grunts and shouts and cold-bloodedly kills Fritz and Waldmann.

The

Monster's crimes eventually reach a climax when he kills the little girl Maria.

(Contrary to that, in the novel he saves a girl !) In this key scene the

Monster meets the little girl, who is not afraid of him despite his

horrible appearance. Together the girl and the Monster playfully throw flowers

into the lake to watch them float like boats. When there are no more flowers

left the Monster grabs Maria and throws her into the water, obviously not

comprehending that she would not float like the flowers. When Maria drowns,

the Monster is shocked and puzzled about what he has done.

Unfortunately

this scene was cut from all releases of the film after 1937. In the censored

version the Monster only reaches out for the child and the following

events remain in obscurity. This cut resulted in a further dehumanisation

of the Monster, since now we do not see the actual killing and the

Monster's reactions. Even worse, crimes like child abuse, child murder or

even rape are implied. Producer Laemmle and director Whale agreed with the

censor to cut the scene but Boris Karloff was very unhappy with it. He

thought that this was the only scene where sympathy towards the Monster

was created and in which one "could suggest a spark of humanity in

the Monster". An indeed, the uncut version displays a little more

empathy for the Monster and gives the audience a chance to identify with

the creature.

Other significant changes concern the reasons for the Monster's

evilness. In Mary Shelley's novel he is the product of his social

circumstances. Although in the beginning the Monster means the people no

harm, they reject and attack him because of his hideous appearance. When he

meets Frankenstein the Monster of the novel explains himself, "I was benevolent

and good; misery made me a fiend. Make me happy, and I shall again be

virtuous" . Whale's film completely drops the idea

of a monster created by social surroundings and walks a completely

different path. In the film a new episode is added in

which Frankenstein's assistant Fritz is supposed to steal a perfect brain

but instead takes that of a

criminal. In a scene preceding the theft Dr. Waldmann holds a lecture in

which he explains why the result of an imperfect brain is a life of

violence and criminality. By making the Monster's aggressive behaviour a

result of an abnormal brain one of the novel's central ideas is completely

removed. The Monster's "behaviour is not a reaction to its experience

but biologically determined, a result of nature, not nurture"

(2). Violence and crime is rooted in personal deficiencies.

Therefore the problem is no longer how to remove violent behaviour but the

violent person - the Monster - itself. The Monster is sub-human and

therefore must be killed. In the end this is achieved by a lynch mob

resembling the Ku Klux Klan. This

implication is also suggested by the mill's blades forming a huge burning

cross, the symbol of the KKK.

Karloff and Colin Clive enjoying a cigarette and coffee |

The screenplay also includes a few more minor changes from the novel.

Victor Frankenstein is now called Henry Frankenstein, his friend Clerval is now

called Victor. There are no more references to Elizabeth being

Frankenstein's cousin. She is now simply his fiancée, which removes any

suggestions of an incestuous relationship. Frankenstein remains more or less

the same he is in the novel, a scientist obsessed with the idea of creating life.

Accordingly, crazed Victor Frankenstein, who sets himself above God,

triumphantly proclaims after giving life to his creature: "Now I know how it feels to

be God!" This act of blasphemy removes him from his family, his friends and his bride. But unlike in

the novel, he changes from a manic scientist, obsessed with the idea of

creating life without the participation of a woman, to a loving husband who

finally gives up his experiments in the dark (3).

Still, there is little chance to identify with Frankenstein, and

viewer sympathy is likely to switch from creator to the Monster. Of

course, Frankenstein's change of mind, his feelings of remorse for

his blasphemy and transgression of nature's boundaries, make Whale's

film work perfectly as an example of conservative morale. The

message is clear: If man sets himself above God, he will only create

evil, which inevitably has to be destroyed. In order to save

himself, he must repent of his sins, join forces against his

creation and return to his family. Therefore Henry Frankenstein is

allowed to survive (unlike the novel's Victor Frankenstein) and the

film gets its Hollywood-style happy ending. |

The creation of Boris Karloff's mask, which has become the ultimate

image of the Frankenstein Monster, is mainly the work of Universal's chief

makeup artist Jack Pierce. Whale, who was also an artist, had drawn

sketches of Karloff, which were closely followed by Pierce. Sketches provided by other

make-up artists depicted the Monster as an alien, a wild man or a robot,

but Pierce and Whale wanted him to have a "pitiful humanity"

(4). In 1939 Pierce revealed how he designed the mask: "I

did not depend on imagination. In 1931, before I did a bit of designing, I

spent three months of research in anatomy, surgery, medicine, criminal

history, criminology, ancient and modern burial customs, and

electrodynamics. My anatomical studies taught me that there are six ways a

surgeon can cut the skull in order to take out or put in a brain. I

figured that Frankenstein, who was a scientist but no practising surgeon,

would take the simplest surgical way. He would cut the top of the skull

off straight across like a potlid, hinge it, pop the brain in , and then

clamp it on tight. That is the reason I decided to make the Monster's head

square and flat like a shoe box and dig that big scar across his forehead

with the metal clamps holding it together." (5)

| Jack

Pierce built an artificial square-shaped skull, like that of "a man

whose brain had been taken from the head of another man" (6). He fixed wire clamps over Karloff's lips,

painted his face blue-green, which photographed a corpse-like gray, and

glued two electrodes to Karloff's neck. The wax on his eyelids was

Karloff's idea. "We found the eyes were too bright, seemed too

understanding, where dumb bewilderment was so essential. So I waxed my

eyes to make them heavy, half-seeing", Karloff explained (7). He wore an undersized suit in order to make his limbs

look longer and heavy boots weighing 13 pounds each in order to produce

his lurching walk. The procedure of applying the make-up was a horrible

experience for Karloff: "I spent three-and-a-half hours in the

make-up chair getting ready for the day's work. The make-up itself was quite painful, particularly the putty on my eyes. There were days when I

thought I would never be able to hold out until the end of the day."

(8) |

Boris Karloff in full make-up

|

"It's alive! Alive!"

|

Stylistically, James Whale's Frankenstein

shows many influences of German expressionism, particularly of films like Das

Kabinett des Dr. Caligari and Metropolis.

Frankenstein's tower and his

laboratory often look as if they were taken

directly out of a nightmare. Walls and stairs are huge and irregular; the

hunchback Fritz and the Monster cast eerie shadows on the walls. A

distinctly dark, morbid tone is also established right with the opening

shots of a funeral and graveyard, where Frankenstein and Fritz steal

bodies for their experiments.

The

highlight of the set design is surely the laboratory. It is stacked

with strange machines, electric devices and bubbling test tubes. The

Monster lying on a platform is lifted to the top of the lab where it is

exposed to lightning. The platform then descends and the first sign of

life of the creature is his moving right hand. Frankenstein's hysterical

cry, "It's alive!" is obviously a reference to Brinsley

Peake's 1823 play Presumption,: There Frankenstein animates his

monster and shouts, "It lives!".

|

|

This film also established the concept that the Monster is brought

to life by means of electricity and lightning. This idea may be taken from Mary Shelley's

introduction to Frankenstein, where she mentions galvanic experiments, and

from chapter two of the novel (1818 edition), which contains the following short discourse

on electricity and galvanism:

"When I was about fifteen years old we had retired to our house near Belrive, when we witnessed a most violent and

terrible thunderstorm. [...] Before this I was not unacquainted with the more obvious laws of electricity. On this occasion a man of great research in

natural philosophy was with us, and, excited by this catastrophe, he entered on the explanation of a theory which he had formed on the

subject of electricity and galvanism, which was at once new and astonishing to me. All that he said threw greatly into the shade

Cornelius Agrippa, Albertus Magnus, and Paracelsus, the lords of my imagination;" (Shelley 1818)

In this and most succeeding Frankenstein films the

creature is exposed to lightning or some other electrical source in

order to give it life. Mary Shelley, however, never goes into detail on

how Victor Frankenstein manages to inject life into his creature. |

Frankenstein (Colin Clive) and his assistant Fritz (Dwight Frye)

in

the laboratory

|

|

Cast & Crew: |

|

| |

|

|

Henry Frankenstein |

Colin Clive |

| Elizabeth |

Mae Clark |

| Fritz |

Dwight Frye |

| The Monster |

Boris Karloff |

| Dr. Waldmann |

Edward van Sloan |

| |

|

| |

|

| Make-up |

Jack Pierce |

|

Writing credits |

Francis Faragoh,

Garret Fort,John Balderston,

Peggy Webling, Robert Florey, John Russel |

|

Music |

Frank Skinner |

|

Cinematography |

Arthur Edeson |

| Producers |

Carl Laemmle jr, E.M. Asher |

| Director |

James

Whale

|

Footnotes: 1 cf.

O'Flinn, Paul. "Production and Reproduction: The Case of Frankenstein". Frankenstein: Contemporary Critical Essays.

Ed. Fred Botting. (London: Macmillan Press, 1995) 33

2 O'Flinn 1995: 36

3 Stresau, Norbert, Der Horrorfilm (Munich: Wilhelm

Heyne Verlag, 1987) 121-122

4

Manguel, Alberto. Bride of Frankenstein. (London: British Film

Institute, 1997) 20

5 Manguel 1997: 20-21

6 Pierce, quoted from Jones 1995: 37

7 quoted from Manguel 1997: 20

8

Jones, Stephen. The Frankenstein Scrapbook: The Complete Movie Guide to the World's Most Famous Monster.

(New York: Carol Publishing Group, 1995) 37

©

1999-2005

Andreas Rohrmoser

|